Local Tales of Antiquarian Acquisition, De-accession, and Salivation.

Wednesday, 25 December 2013

Book 03: Images of Faith

I ordered this via Amazon on a lark since it was reasonably priced at $4.50. It turned out to be one of the best written catalogs concerning the history, trade of ivory in the Philippines and its uses as ecclesiastical artifacts.

Images of Faith was published by the Pacific Asia Museum last 1990. Though simple in design, the articles written by Regalado Trota Jose is so rich and precise that one could mine a lot of information from it. From the sources of the ivory, the reason why most of the pieces can be found outside the Philippines, the Chinese features in the sculptures to the last ateliers of the previous century, Mr. Jose elaborated on such interesting aspects that after reading his paper, one would have gained an encompassing sense of knowledge on the subject.

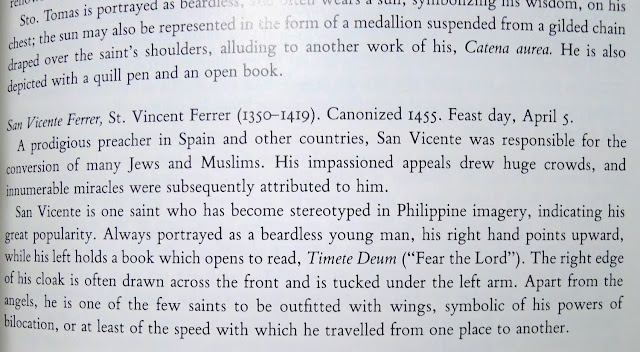

The author also gave lots of time on the identification on the different saint types from the different manifestations of the Virgin, to the positions of the Baby Jesus to the different saints of the Holy orders. He made sure to include each attribute so to help ease in the identification of a particular saint. Such meticulousness in his descriptions without deteriorating into pedantry is really really commendable. Actually, after going over his research, you might not care anymore about the pictures.

So is it worth getting if you're into santo collecting? Yes!

Saturday, 21 December 2013

Book 02: A Heritage of Saints

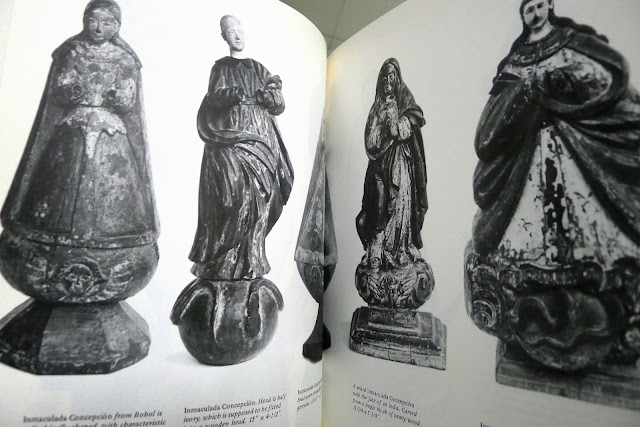

I simply love Esperanza B. Gatbonton's A Heritage of Saints: Colonial santos in the Philippines. It's richly textured without sounding like a dissertation paper. And her collector's passion in her words is tempered by the need to elaborate and organize the different saints and relics that abound in the Philippines. This was published during the heyday of the 70s wherein religious antiques of great quality still can be found in the shops along Mabini and del Pilar. So, it is safe to say that this book is a product of the madness of antiquing during this period. Now, you would be consider lucky if you can find cheap yet authentic ivory pieces in the shops.

The book first delves into the history of the Filipino santos and the cult that it has spawned. From the conversion of the native heathens to Catholicism to the refashioning of the idols into household saints, it proves that our form of Christianity is still a part of our precolonial temperament. She also talks about the art and craftsmanship of the santero or saint-maker and also the specific saint types like San Roque (St. Roche) to San Vicente (St. Vincent). Her writing is vivid yet rich with details. More importantly, the pictures are there to remind you that your santos in the sala may or may not be the real thing. And those in the photos are those pieces that may have gotten away.

Books (unlike catalogs) specifically on antique santoses/saints are

really scant and rare. So far I have two out of the three better known works devoted to Philippine santos thanks mainly to the convenience of the web. I am still searching for a reasonably priced Fernando Zobel de Ayala's Philippine Religious Imagery (Ateneo de Manila Univ., 1963). A diligent search in the net is a must if you're truly passionate in collecting antiques. Not just for the objects but the books that delve into the subject. And Mrs. Gatbonton's book is a treasure indeed. And procuring one in near-mint condition is joyous indeed.

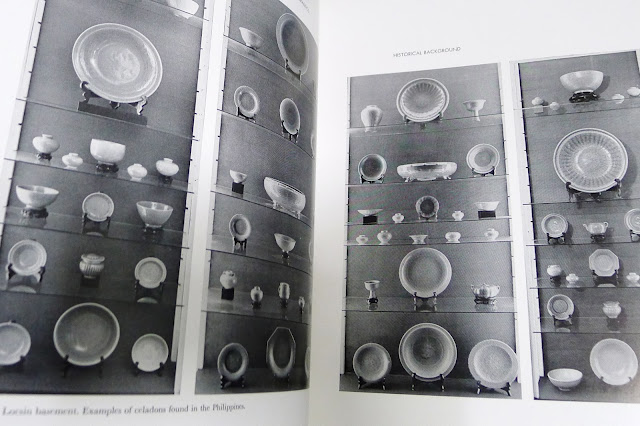

Book 01: Oriental Ceramics Discovered in the Philippines

If there’s a book that every Filipino ceramic collector should have in his/her library, this is the one. This is one of the earliest and most cited work when it comes to ceramics and Philippine terrestrial archaeology.

Written during the plentiful year of the 60s by famed

artist-archaeologist Leandro Locsin, Oriental Ceramics traces the origins of

the trade, the history and the variety that they unearthed in Sta. Ana and

Calatagan. Aided by Robert Fox and the

National Museum, Locsin has managed to systematically study and catalog early

trade ceramics in a way that gives us a clear glimpse of the richness of precolonial Philippine

society.

Presently, there has not been a book of this magnitude and scale ever published. Even the famed author on Asian ceramics, Roxanna Brown, acknowledged in her book The Ming Gap and Shipwreck Ceramics in Southeast Asia (The Siam Society, 2009) that the Sta. Ana and Calatagan finds were important because they constitute large burial finds that do not have a single Chinese blue&white ceramic.

Published by Tuttle in Japan in 1967, Oriental Ceramics has the marks of being a collector's book. Hardbound in a blue buckram cover with gilded lettering, the volume is worth the $22.50 retail price. The paper used was heavy glossy paper similar to those mid-century US encylopedias we have in the house. There are 228 plates and 89 in full color. Color printing back then must have commanded a premium price. The photos are crisp and well lighted. For collectors, the pieces featured inside are great reference to cross-check any collection. Mostly, the pieces are Thai, Vietnamese or southern Chinese. If you're looking for Ming, you might want to check another book.

Famed historian Ambeth Ocampo collected and sold this volume. He recounted in the September 2006 newsletter of the Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines:

" I was so disinterested in ceramics that I sold two copies of the rare book, Oriental Ceramics Discovered in the Philippines by Leandro and Cecila Locsin. When I got hold of a third and fourth copy in 1999 and actually leafed through them, I realized very late that any study of Philippine pre-history inevitably touched on ceramics. These were so important that the pioneering pre-historian H. Otley Beyer even wrote an article on ‘The Philippines in the Porcelain Age’ (roughly the 9th to the 16th centuries). ... The more I read, the more interested I became and when I went into antique shops, I would give ceramics a second look and realize that they were objets d’art and not just traces of our history."

This is why if you are absolutely serious about collecting antique ceramics in the Philippines, then try to procure this book.

Published by Tuttle in Japan in 1967, Oriental Ceramics has the marks of being a collector's book. Hardbound in a blue buckram cover with gilded lettering, the volume is worth the $22.50 retail price. The paper used was heavy glossy paper similar to those mid-century US encylopedias we have in the house. There are 228 plates and 89 in full color. Color printing back then must have commanded a premium price. The photos are crisp and well lighted. For collectors, the pieces featured inside are great reference to cross-check any collection. Mostly, the pieces are Thai, Vietnamese or southern Chinese. If you're looking for Ming, you might want to check another book.

Famed historian Ambeth Ocampo collected and sold this volume. He recounted in the September 2006 newsletter of the Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines:

" I was so disinterested in ceramics that I sold two copies of the rare book, Oriental Ceramics Discovered in the Philippines by Leandro and Cecila Locsin. When I got hold of a third and fourth copy in 1999 and actually leafed through them, I realized very late that any study of Philippine pre-history inevitably touched on ceramics. These were so important that the pioneering pre-historian H. Otley Beyer even wrote an article on ‘The Philippines in the Porcelain Age’ (roughly the 9th to the 16th centuries). ... The more I read, the more interested I became and when I went into antique shops, I would give ceramics a second look and realize that they were objets d’art and not just traces of our history."

This is why if you are absolutely serious about collecting antique ceramics in the Philippines, then try to procure this book.

Saturday, 16 November 2013

Asian Influence on a Philippine Cup

A couple of years ago when I contracted the "collecting" fever, I got hold of several precolonial pottery that were on offer in a couple of antique shops. I had to sift through what must have been fakes and restored items and thankfully, got hold of some that were choice pieces. That is, until several days later, I noted that one of the pieces had a restoration mark which I had initially missed.

This goblet or chofa or cup is one of those choice pieces I got. It's quite light, the potting quite thin and it has that iron oxidation on the clay. This I think was sourced from one of the surrounding islands of my province that has been a rich source of precolonial pottery. No restoration so far.

This is the only precolonial object I have encountered that is in a goblet form. Maybe funerary, maybe utilitarian, who knows what purpose this cup is for. The strange thing about this is that the design is not indigenous to the islands. The motif could be either Ming or Vietnamese with the wide lotus petals on the neck. If it were indigenous, it would sport linear or curvilinear or chevron designs instead, not stylized floral. Hence, this must have been created during the Age of Contact probably between 12th-15th century wherein Filipinos have a great deal of trade with China and Annam and Sukhothai. Ceramic goods that were traded may have become the basis for the form and design of such antique. Until then, more study should be made in this direction. And more publications should be read.

Clearly, it's too strange, too specialized, too anachronistic for this to be judged as a fake.

Similar types of precolonial pottery are seen in one of the volumes of Filipino Heritage.

Monday, 11 November 2013

Shards of Ming Dynasty Ceramics

These are some of my representative pieces that I've asked my runner to collect. Collectors CAN ask for a ridiculously low price for these loose chunks of ceramic history. Runners and dealers tend to value Ming shards more because they wanted these glued, restored, or recreated and they sell them for anything from a hundred to a couple of thousand pesos. Oftentimes, if the pieces are too broken up, these get to be left out and eventually ignored. For me, I share the same sentiments with those who create jewelry pendants out of these blue&white pieces, for these seemingly worthless objects can become informative and valuable.

Valuable in fact that in China (and on Ebay), real Ming dynasty shards (or sherds) are now being sold for a hefty sum. Reason? You get to study the glaze, the potting, the design, the type of pigment used, etc. Aside from looking at photos inside ceramic catalogues, having the real physical object in your hand is double the learning process. And with it, you get to have a sense of what is fake and what is not. Even if it's not the whole piece, you get to know the feel and the glaze and differentiate if whether it's from an Imperial kiln of Jingdezhen or from an Export Zhangzhou kiln.

Isn't it a beauty to see the cross-section of a Ming dynasty charger? No need to break an expensive piece, just ask for a shard instead.

Sherds of Song Dynasty

These are a few of the Song or Sung Dynasty sherds that I've collected these couple of years. I'm saving these for some architectural project in the far far future. From Lonquan celadons, to bluish Northern Song and to brownish Southern Song, these shards represent actually the variety of ceramics that's buried underneath the Philippine soil. Collecting these are more for personal enjoyment knowing that long ago, these were used by precolonial Filipinos. In these you tend to appreciate the potting, the glaze, the cracleur and the art of Chinese ceramics.

Friday, 1 November 2013

A Guangdong Brownware Jar with Dragons

This small brownware jar is part of the lot I bought along with the Ming chicken water dropper. This kind of jar is quite strange because of its size. It's approximately ~15-20cm and looks like a small earthenware vase. It has four pressed lugs with one lug chipped off. It has this brown glaze with signs of glaze degradation.

There are two stylized dragons adorning the body and around it are incised wave-like pattern. Dragons are more predominant during the Ming era as opposed to the unadorned Song dynasty vessels which concur the age of this item. Thus, looking at the motif and the make, I would say this small jar is from the Guangdong area of Southern China during the Ming dynasty.

It is similar to the one published by Cynthia Valdez in her seminal book: A Thousand Years of Stoneware Jars.

It does look nice when it sits on top of your table or desk, doesn't it?

Wednesday, 30 October 2013

Santos Series 01: San Ramon & San Roque

The photo above is purported to be a 19th century

or early 20th century carved santos. I could be wrong but this one looks like San Ramon Nonato because of the white chasuble. This

piece came to me a year ago from another island that is famous for its delicacies. It seemed that the previous collector-owner wanted to dispose this along with the ubiquitous

San Vicente Ferrer, but among the lot, this San Ramon is the best carved. San Vicente, San Roque and Virgin Mary

Bohol-style are more common than the rest, so getting another saint type is

desirable for it gives one’s collection

variety. This means that if you see a

San Agustin or a Sta. Ana or a Sta. Teresa de Avila, get it for more often than

not, you won’t find another one of the same type in the next years or so.

This 2nd santos is San Roque (St. Roche). This was sourced from one of the outlying

towns in my province. Provenance wise,

this came from the prominent Callate family whose nonagenarian matriarch had

passed away a year ago. So, one

of the remaining heirs who converted to Non-trinitarian Protestantism was only

too happy to dispose of their saintly heirlooms apparently in a bid to earn

more shopping mileage. But their issues

are not mine, so whatever item they want disposed I shall gladly take.

Anyway, this San Roque was originally a table top figure.

All San Roque statues consist of three parts: San Roque, the angel bearing a

scroll, and a dog. In my case, probably

because of wood deterioration, the seller cannibalized the set and mounted the

saint and the angel onto a felt-backed wooden frame. Such frames are common during the

70s-80s.

What I love about this is that the figure is an original

from the 19th century, with just the right amount of folk naiveté. The saint is well-carved as seen in the

beard, the flow of the fabric, and the proportion of the body. The master-carver must have some training in

order to execute such minor expertise.

The angel, however “folkish”, is also original with intact

patina. It is important that when collecting Philippine santos, one must try to

preserve the patina or choose one that has not been sanded over nor

retouched. However, there are pieces that were

painted over several times because of tradition should be reconsidered for

this would add another layer of story to the piece instead of destroying it. Caveat emptor still precedes any decision whatsoever.

Some Tips for collectors:

If you encounter a saint type that is rare and uncommon,

get it for chances are, you won’t stumble a similar type on the next antiquing

expedition.

If a veteran collector or an old family is unloading their goods, check it out. Their items may be choice pieces since they bought it during a time

of plenty.

Do not 100% believe the provenance of your antique dealer or

runner. A lot of times, theirs are just hearsays. Believe it though if you bought the item directly from the owner.

Do diligence check on all desired items. Check for faults,

restorations, fakes, etc.

Try to avoid santos that had been sanded over / intentionally excoriated whereby the patina of the poor thing has all but disappeared.

Friday, 25 October 2013

A Filipino Ceramic Water Filter or Banga or Tapayan

My suki-runner brought this to my house just this morning. His friend was trying to unload this. Provenance-wise, this came from a family who had rich ancestors but now have succumbed to the vicissitudes of life.

He lugged in an American colonial-era (1899-1945) ceramic water filter. The condition was

| A sample of an earthenware banga or tapayan (dont.blink.ph) |

The filter is made from indigenous Philippine clay much like the "banga" of old. Since the country doesn't have a ceramic industry like in Delft or China, a lot of local filters are made of clay. Unlike the banga, this one has a filtering mechanism where impurities are cleaned out. The poor unfortunately had to contend with the earthenware jar or banga or tapayan for storage. Wasn't there a cholera epidemic during the 1910s? Oh well.

The item has a smooth white-washed outer finish, with flecks of remaining brown paint, labeled with black ink. The body is made of three parts: the cover, the upper reservoir where one pours in the unfiltered water and the lower reservoir which holds clean water. The upper reservoir fits like a hat on top of the lower part as seen in the middle rim. There is also a brass spout which acts as the spigot, or the "tuburan" or "gripo".

The label here is:

Dizon Filtro Radinmetor

Reg. Trade Mark

Pat. Apld. (Patent Applied?) For USA & Foreign Countries

C.M. Dizon Mxxxxxx

Porac, Pamp. (Pampanga), P.I. (Philippine Islands)

I have deduced that this water filter is from Pampanga during the American period since the use of the initials PI as opposed to RP for Republic of the Philippines in which the latter was used during the Republic years of the 50s-60s. Noting the ingenuity of the maker which I think was his reaction to the lucrative importation of European ceramic water filters, this particular filter must have been made during the 30s or 40s. Why? Think about it. The Philippine Commonwealth era heralded a period of peace and prosperity for Filipinos. Unlike the early years where importation was rampant marred by the Philippine-American war, and where European ceramic filters were expensively exclusive, Mr. C.M. Dizon (Celestino M. Dizon?) was able to build up capital and build a local factory for making cheaper alternatives using local materials. This is perhaps why upper-middle class landowners could then afford to buy this type of luxury.

As the water goes into the upper reservoir, two limestone like handles act as filters, which in this case one has been broken off (to my chagrin).

What got me excited is the

Thursday, 17 October 2013

A Set of Cosmetic Containers

Couple of years ago, the owner of a rundown antique store in my city has these ceramic cosmetic containers displayed in one of her glass curio cabinets. These ranged from the late Ming to the Yuan to the Qing dynasty. They are an odd lot with their covers already gone. Collectors, especially old matronly ones, favor these types because of their size. Well, anecdotally speaking, that is.

So, the owner sold me this entire lot for $20. I was happy with it since collectively, they look good in my cabinet.

However, some tuition fee was inevitable. I reexamined a few and I suspected that these were modern copies- they looked as if they were machine made and the glaze was too modern for my taste (no cracleur, no rust spots, no potters wheel mark). Well, caveat emptor I guess.

Which ones are fake, can you guess?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)